| Contact us |

| Try wildfowling |

| Club merchandise |

| Wildfowl art |

| Wildfowling books |

| Join KWCA |

| Search |

Safety - The Killer Storm Surge

|

Although we are never likely to witness the Seven-like bore racing up the Thames Estuary to cause catastrophic flooding in London, as portrayed in scenes from the BBC's 'Flood', the surge tide does present a very real threat to the Wildfowler. For those of us who frequent the intertidal zone for recreation, even the smallest of storm surges can be life threatening. |

|

|

This animation shows the progression of a storm surge around the coast of the UK. The largest positive surge is coloured red, while the largest negative surge is coloured blue.

See how the water is driven away from the east coast only to be replaced by a massive storm surge flooding back a few hours later.

If a high tide occurs during a large positive surge then coastal flooding is likely. |

How do these storm surges occur?

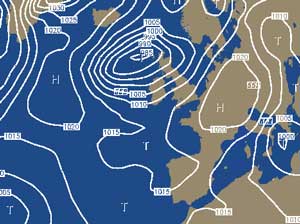

The North Sea surge is created by the winds

and low atmospheric pressure associated with a depression developing in

the Atlantic Ocean and tracking towards Scotland. Beneath the depression

the sea is sucked up into a hump, small at first but stretching over a

footprint of perhaps a thousand miles diameter. The gale force south-westerly

wind generates a positive surge current which pushes water onto the west

coast and a negative surge pushing water away from the east coast; importantly

for us, out of the Thames Estuary. Any high pressure over the southern

North Sea in the proceeding days will compound the problem by also driving

water away from our Estuary.

|

|

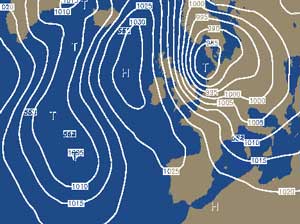

As the weather system passes to the North of Scotland, its Atlantic surge is squeezed into the North Sea, building in height, it joins forces with the expelled water from the southern part. Together, driven by low pressure and the now north-westerly gale, they surge down the east coast and into the Thames and Medway rivers, bringing with them, potentially catastrophic flooding.

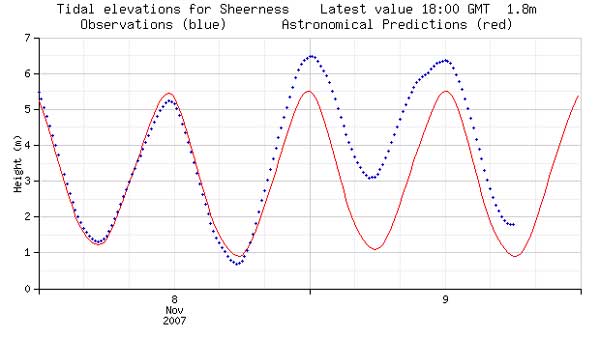

Here we see the effect of a storm surge,

measured by the Sheerness tidal gauge.

Here we see the effect of a storm surge,

measured by the Sheerness tidal gauge.

In this case, a very lucky

escape!

Firstly, note the previous tide's

low water, the negative surge is only slightly below prediction. In the

worst case, this could be 2 metres lower, water that would then add to

a later surge. Secondly, it does not coincide with a high spring tide,

and thirdly, the bulk of the 2-metre surge arrives at low water.

Imagine the worst case scenario.

The negative surge at a maximum, later doubling

the 2-metre positive surge. Coinciding with high water, it adds 4 metres

to the highest spring tide of the year. If the depression continues to

track south, storm force north-easterly winds add two-metre on-shore waves.

Catastrophe! A tide, 5 metres above prediction, overwhelming flood defences

and devastating thousands of acres of low-lying land.

But it does not take this '1000 year' event

to drown the unwary Wildfowler.

Caught out on low salting, even the smallest of surges can pose a very

real danger.

One-metre surges are very common, occurring with alarming frequency; perhaps

six times a year!

Watch out for them! If you do not see them coming, one day they will catch you out!

Check the lastest Storm Surge Forecast now!